Daimler Truck: Hydrogen is “Europe’s biggest opportunity” and must act now on hydrogen trucks

Daimler Truck has issued a direct warning to European policymakers: if the continent wants to decarbonise road freight, maintain energy resilience, and stay competitive in vehicle technology, then hydrogen infrastructure must be built now – not in five years’ time, and not only after the limits of battery-electric solutions become apparent.

Writing in a detailed piece for Germany’s Hydrogen Week, Dr Andreas Gorbach, the company’s board member for truck technology, argued that hydrogen will be essential for delivering net-zero transport.

Battery-electric trucks remain a core part of the transition, he said, but they can’t meet every use case – particularly in long-haul operations where range, payload, and uptime all matter.

“Those who want to lead the transport of the future don’t choose either-or”, Gorbach wrote. “They choose battery and hydrogen.”

Batteries are well suited to some applications – but not all

Daimler isn’t shying away from battery-electric. Indeed eleven of its trucks are already in series production, and its long-haul eActros 600 is set to enter production later this year.

For urban deliveries, short-haul routes, or depot-based logistics, battery power makes a lot of sense. The trucks are efficient, the infrastructure is coming, and many fleets are already making the switch.

But long-distance freight is a different challenge altogether. High payloads, energy-intensive refrigeration, demanding routes and tight turnaround times all place demands that batteries – and the grid – can struggle to meet.

To illustrate the point, Gorbach points to charging infrastructure. Delivering a fast charge to just ten long-haul trucks at a motorway rest stop requires around 10 megawatts of power – equivalent to the electricity demand of a small town.

And rolling that out across Europe’s freight corridors isn’t only expensive, it takes time. In many areas, that level of grid reinforcement could take a decade or more. In the UK, for instance, some sources say the waiting time for a depot grid connection can start at 15 years.

“We don’t have that time,” he said. “2030 is less than five years away.”

Hydrogen is a necessary complement

Gorbach argues that hydrogen fuel cell trucks aren’t there to replace battery-electric models, but to fill in the gaps where batteries reach their limits.

Refuelling is quick, the driving range is long, and the infrastructure – when built – operates much like today’s diesel pumps, without the constraints of megawatt-scale chargers.

Hydrogen combustion engines also form part of the picture. Gorbach points to their potential in high-payload, low-mileage applications such as construction and specialist logistics.

These engines offer robust packaging, lower system costs, and minimal installation complexity – making them particularly well-suited to demanding off-grid use cases.

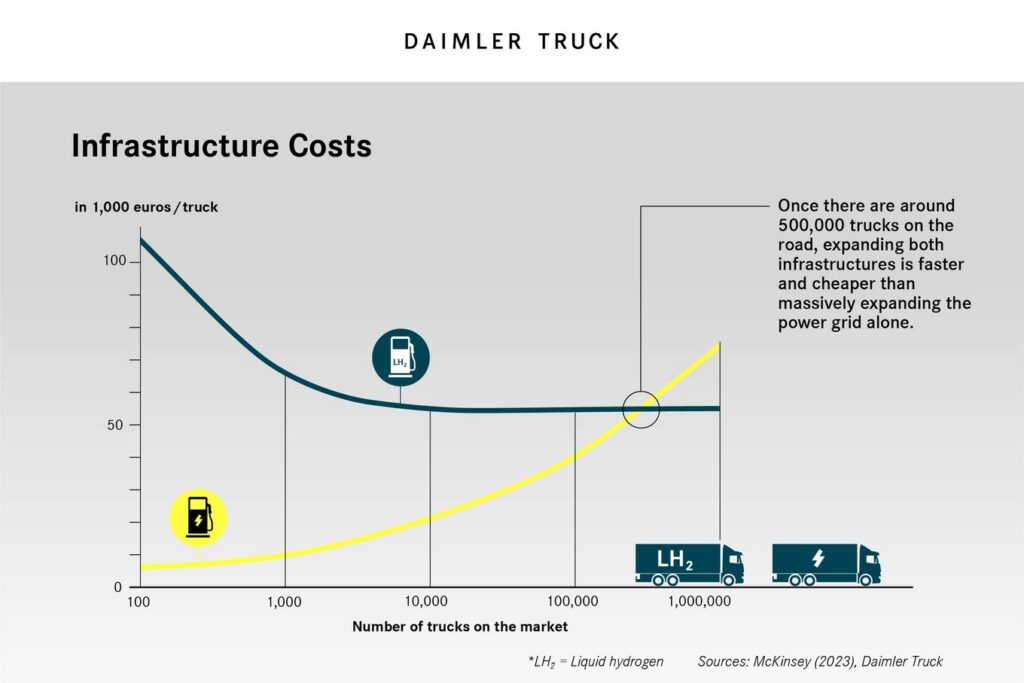

According to Daimler, building both types of infrastructure in parallel is not only practical but even more cost-effective than trying to expand the electrical grid alone to serve every use case.

Daimler’s hydrogen trucks are already in use

Daimler says hydrogen trucks are not a distant ambition, with its fleet of rigs having already covered more than 15 million kilometres across Europe in real-world conditions.

Five transport companies are currently running early prototypes of the Mercedes-Benz GenH₂ Truck, with a wider trial of 100 vehicles scheduled by 2026.

These trucks are powered by fuel cells from Cellcentric – Daimler’s joint venture with the Volvo Group – which is in the process of building one of Europe’s largest dedicated fuel cell production facilities, located in southern Germany.

Alongside this, Daimler continues to explore hydrogen combustion technology as a complementary option – particularly in duty cycles where ruggedness, cost and simplicity outweigh long-distance range.

Daimler says the next generation of trucks is already in development and sees fuel cells as a core part of its long-term zero-emissions strategy.

Cost is coming down – and €5/kg is the tipping point

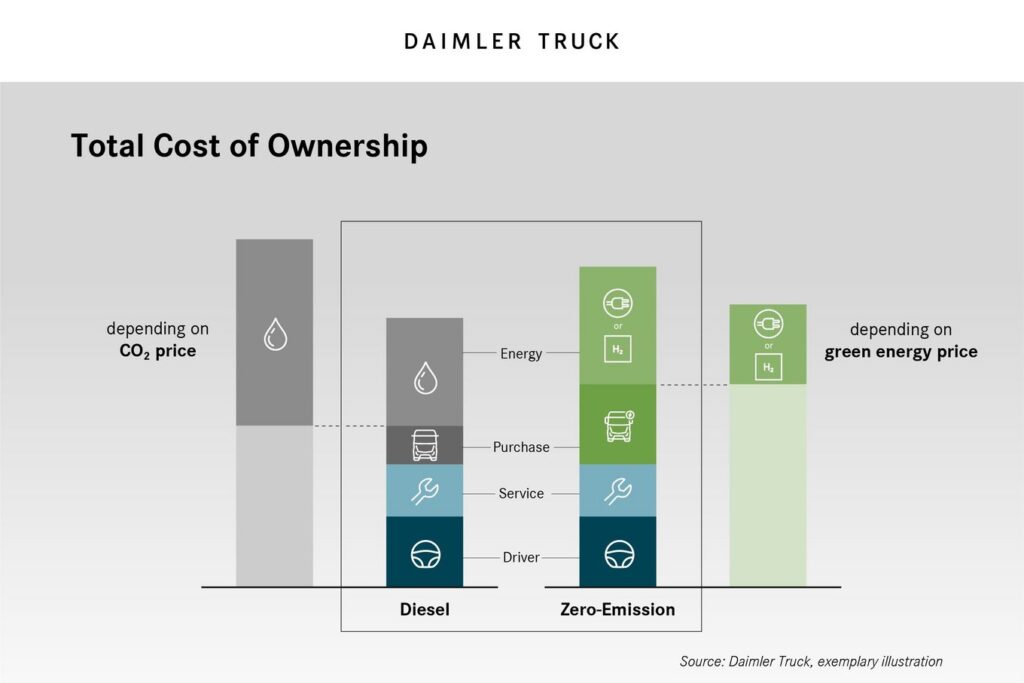

Hydrogen remains more expensive to run than diesel today, but Daimler believes that will change quickly as supply scales up and regulations like RED II begin to take effect.

Gorbach says the tipping point for commercial viability sits around €5 per kilogram of hydrogen – a figure he expects the transport sector to reach by the end of the decade.

Production costs are already falling, and in some export-oriented projects – such as those in Saudi Arabia using large-scale wind and solar – hydrogen is being produced at around €2/kg.

These projects aim to ship green ammonia or liquid hydrogen into global markets, where economies of scale could drive down costs for industrial and transport users alike.

In the meantime, Gorbach calls for pragmatism on sourcing. While green hydrogen remains the goal, he argues that early adoption should focus on reliability and availability, not purity.

“Hydrogen must be green – at least in the long term. During the ramp-up phase, the focus should be on reliable availability – regardless of colour,” he wrote.

Efficiency debates are missing the point

Gorbach also takes aim at one of the most common criticisms of hydrogen: its lower overall efficiency compared to batteries.

He doesn’t deny the numbers, but says the framing is too narrow.

The real question, he argues, isn’t how many kilowatt-hours reach the wheels – it’s what the system can actually deliver when it’s needed.

Germany, for example, curtailed around 10 terawatt-hours of renewable electricity in 2024 because the grid couldn’t absorb or store the surplus.

That’s the equivalent of roughly €2.8 billion in wasted power. Hydrogen, which can store and transport energy over time and distance, could have turned that waste into value.

“Unused renewable energy has an efficiency of zero,” Gorbach writes.

From Daimler’s perspective, hydrogen isn’t just a drivetrain solution – it’s a way to balance the energy system and make better use of the renewable power Europe already produces.

Freight emissions are rising – and targets are looming

Europe’s freight sector includes more than six million trucks, with 800,000 operating in Germany alone.

Together, they account for around 7% of the EU’s total CO₂ emissions – a figure that continues to rise as transport demand grows.

Under current legislation, truck manufacturers must cut emissions from new vehicles by 45% by 2030 and 65% by 2035.

Gorbach says it will be extremely difficult – if not impossible – to meet those targets with battery-electric alone, given the current pace of grid development and the physical limitations of battery-based drivetrains in certain applications.

That’s why Daimler continues to press for hydrogen to be treated not as an optional extra, but as a vital part of the freight decarbonisation toolkit.

Europe still leads – but not for long

Daimler also warns that Europe’s industrial lead in hydrogen and fuel cell technology is under threat.

China in particular already has more than 30,000 hydrogen vehicles on the road and over 400 hydrogen refuelling stations in operation.

By 2030, that’s expected to reach one million vehicles and 1,000 stations.

Europe still has the edge on system integration, vehicle engineering, and fuel cell development – but Gorbach says that won’t last without action.

“While Europe has already fallen behind in battery cell production, China has not overtaken us in fuel cells and hydrogen engines. Not yet.”

500,000 jobs – if the EU gets it right

According to Daimler, a hydrogen economy at scale could create as many as 500,000 skilled jobs across Europe by 2030 – spanning truck and fuel cell production, electrolysis, energy logistics, and infrastructure development.

But Gorbach says that potential will only be realised if governments provide a stable policy framework, give investors confidence, and stop treating hydrogen as something to debate rather than deliver.

“Many companies are ready to go,” he writes. “What’s missing is a clear political framework that enables investment and gets the market moving.”

Final word

Daimler’s message is clear: the trucks are here, the technology is proven, and the investment is already underway.

What’s needed now is for governments to create the conditions that let hydrogen scale – and to recognise that battery-electric alone won’t decarbonise Europe’s freight sector on the timeline required.

“Those who keep the world moving carry responsibility. For the economy. For society. And for the climate.”

Europe still has the chance to lead. But that window won’t stay open forever.