“Failure is not an option” – Daimler Truck exec’s brutal takedown of EU’s broken truck strategy

It’s not often that a senior industry figure delivers such a blunt – and frankly scathing – assessment of Europe’s climate and transport policies.

Yet that’s exactly what Dr. Andreas Gorbach, Board Member at Daimler Truck AG and Head of Truck Technology, has written in his published piece today, titled “FAILURE IS NOT AN OPTION – Why we all depend on commercial vehicles. And what needs to happen now.”

His warnings paint a stark picture of commercial vehicles’ central role in our economy – and of the looming crisis if we don’t drastically accelerate zero-emission infrastructure.

Dr. Gorbach’s commentary underlines the urgency of this transition – but it also issues a blistering critique of how policymakers are (or aren’t) supporting that shift.

The stakes for Europe’s commercial vehicles

“Trucks and buses are and will remain the backbone of our economy and society”, Dr. Gorbach writes.

It’s easy to forget just how heavily we rely on these vehicles until our packages arrive late or we see empty shelves at the supermarket.

But Dr. Gorbach’s message is clear: without commercial vehicles, our lifes grinds to a halt.

- 70% of everyday products travel by truck.

- 6 million trucks and 900,000 buses operate across Europe daily.

- By 2040, Germany’s freight transport by truck is projected to increase 34%, reflecting similar growth across Europe.

In other words, there’s no scenario – no matter how idealistic – that sees commercial vehicles disappearing from our roads.

The question, instead, is whether those essential vehicles will run on diesel or clean energy.

The urgent case for battery and hydrogen

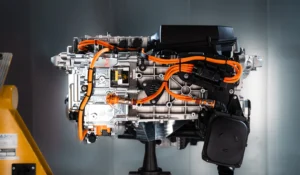

Naturally, Dr. Gorbach urges a rapid transition to zero-emission technology. He clarifies that battery-electric drives are “ready” for certain use cases, but hydrogen will play a crucial complementary role – particularly when it comes to meeting heavy power demands and in travelling long distances.

“Depending on the transportation task, battery or hydrogen (with fuel cell or internal combustion engine) can be the more economical solution”, he explains.

The point is: there is no one-size-fits-all approach. Heavy transport is simply too diverse – some routes work brilliantly with battery charging infrastructure, and others demand long-range hydrogen or alternative carbon-neutral fuels.

Why batteries alone can’t carry all the load

Beyond the simple fact that trucks aren’t cars, Dr. Gorbach underscores startling energy statistics that highlight the necessity of hydrogen alongside battery-electric solutions:

- Converting all six million trucks in Europe to battery-electric would require around 350 TWh of green electricity per year.

- For comparison, Germany’s total electricity demand in 2023 was about 500 TWh. In other words, electric trucking alone would consume nearly three-quarters of Germany’s annual electricity.

- The high-voltage grid expansions needed for such a massive battery-charging network would be time-consuming and prohibitively expensive.

- A single public rest area capable of charging multiple long-haul trucks at once might need up to 10 MW of power. Planning and building that kind of facility often takes up to ten years.

“Battery-electric vehicles alone will therefore not be able to decarbonise at the speed required to achieve the European CO₂ targets for trucks”, Dr. Gorbach bluntly observes.

While Daimler Truck is already delivering electric models (like the first series-produced Mercedes-Benz eActros 600 recently handed over to customers), Dr. Gorbach clearly believes a sole reliance on batteries is unrealistic for meeting CO₂ deadlines.

Hydrogen’s worldwide potential

Europe’s trucking crisis is not just about tailpipes – it’s about energy. Dr. Gorbach emphasises that a global trade in green energy – particularly hydrogen – will develop independently of the commercial vehicle industry, much like the current global trade in oil and gas.

He also points out that “there is enough sun and wind in the world to produce enough hydrogen to cover the entire demand”, and when hydrogen is produced in sunny or windy regions, the higher efficiency at the production stage compensates for any conversion losses, resulting in a “sun-to-wheel” efficiency that matches that of battery drives.

For commercial vehicles specifically, Gorbach calls hydrogen “the ideal technology to complement battery-electric drives”, noting that depending on the transportation task, either battery or hydrogen (via fuel cell or internal combustion engine) can be more economical.

Moreover, he argues that building out charging and refuelling networks for both battery and hydrogen solutions is less costly and faster to implement than dedicating massive resources to just one technology.

There is a massive political and economic benefit to hydrogen adoption, too: Europe is a leader in hydrogen and fuel cell technology.

In contrast to battery cells, Europe can be the global technology leader here in the long term. Thus, an investment in these technologies is an investment in Europe’s future competitiveness.

Infrastructure: The glaring, underfunded problem

One of Dr. Gorbach’s sharpest criticisms is directed at the sluggish pace of infrastructure expansion:

- 35,000 high-capacity charging points and 2,000 hydrogen refuelling stations for heavy-duty vehicles are needed by 2030 to meet EU CO₂ targets.

- Right now, Europe has fewer than 1,000 adequate charging points for heavy vehicles.

- Hydrogen refuelling infrastructure is lagging even further behind.

“From now on, around 500 new charging points will have to be built every month”, Dr. Gorbach notes, calling the current rollout “far too slow”.

He lays much of the blame at policymakers’ feet, pointing out that high-voltage grid expansion and hydrogen refuelling sites depend on aggressive government action.

Many are precisely calling for a pan-European strategy – and meaningful state investment – to accelerate hydrogen stations along the continent’s major trucking corridors.

Draconian penalties without support

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Dr. Gorbach’s critique is his focus on regulatory inconsistency.

He highlights a paradox: while truck manufacturers are mandated to hit ambitious CO₂ targets, they lack direct control over the core factors that drive adoption – namely, energy prices and infrastructure.

“Manufacturers therefore do not have full control over whether they achieve the specified CO₂ targets for 2030”, he warns, noting that penalties for missing these targets are “draconian” – ten times higher than for passenger cars.

At the same time, Europe’s top truck makers still must provide diesel vehicles, because customers running tight profit margins can’t always switch to zero-emission fleets overnight.

This regulatory mismatch, Dr. Gorbach argues, easily opens the door for non-European competitors who have lower production costs and fewer bureaucratic hurdles.

Calling out to policymakers: “Failure is not an option”

Dr. Gorbach’s article ends with a clear set of demands – ones that we believe Europe’s decision-makers would be wise to heed:

- Tie CO₂ targets to infrastructure expansion & CO₂ toll

In other words, ensure that regulations forcing lower emissions come hand in hand with actual fuelling and charging solutions. Otherwise, the system sets manufacturers (and Europe’s trucking ecosystem) up for failure. - Credit carbon-neutral fuels

Rather than complicating matters with vehicle-by-vehicle verifications, allow recognised carbon-neutral fuels (like HVO or e-fuels) to count toward CO₂ targets – especially crucial in industries where full electrification just isn’t feasible yet. - Massive infrastructure investment

Revenues from truck tolls – Germany alone collects around 15 billion euros – should be channeled directly into building out fast chargers and hydrogen stations for buses and trucks. - Streamline regulations

Dr. Gorbach points out that the truck industry is among the most heavily regulated sectors, navigating over 150 EU regulations and 30 directives. Bureaucratic red tape slows innovation and technology adoption – exactly what Europe can’t afford right now.

Opinion

If hydrogen is going to power the next generation of logistics and transportation, Europe needs a robust infrastructure strategy – fast.

Dr. Gorbach’s piece is both a wake-up call and a rallying cry. He’s not arguing against ambitious climate goals; he’s emphasising that goals alone won’t cut it without the infrastructure and economic incentives to get there.

The underlying message: if European policy doesn’t catch up to the reality on the ground, we risk ceding leadership in zero-emission trucking to other global players.

And that’s not just a missed economic opportunity – it’s a major blow to Europe’s climate ambitions and energy independence.

“If we do not change anything, zero-emission vehicles from other parts of the world will enter European markets precisely when European manufacturers are faced with draconian penalties”, Dr. Gorbach writes, pulling no punches.

And frankly, I applaud his frankness. It’s time for governments to confront the challenge head-on – empowering commercial vehicle makers with supportive regulations, realistic timelines, and the infrastructure to match.

Europe’s decision-makers have a choice: fix this now or watch their own industries collapse under the weight of bad policy.

Because, as Dr. Gorbach so succinctly puts it, “failure is not an option”.