Industry giants tell Brussels: €8 hydrogen or Europe loses the truck race

Europe’s hydrogen truck ambitions risk being stranded unless fuel prices halve and policymakers stop stacking the deck in favour of batteries, according to a new strategy launched in Brussels yesterday.

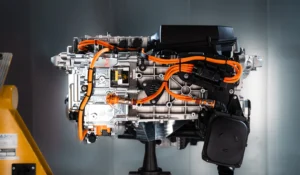

The Global Hydrogen Mobility Alliance (GHMA) – a coalition including Daimler Truck, BMW, Air Liquide, Bosch and TotalEnergies – used EU Hydrogen Week to present its Market Activation Strategy.

The report, backed by a companion industry position paper, calls for immediate intervention to make hydrogen viable for heavy goods vehicles.

Trucks before talk

Hydrogen trucks, the Alliance argues, are technically ready but economically blocked, and Europe must get several thousand HGVs on the road by 2030, supported by stations built at the right scale.

At present, GHMA notes, Europe has around 250 hydrogen refuelling sites, but most were designed for cars. Many operate at well below capacity – often under 15% – which pushes up the operating cost per kilo of hydrogen dispensed.

A modern, well-utilised truck-scale station can run at around €2/kg in operating cost, according to the Alliance, but smaller, under-loaded sites can be closer to €10-20/kg. That inefficiency feeds directly into the high retail prices fleets currently face, with most pumps still charging more than €15/kg.

This is why GHMA insists the minimum threshold for new stations should be 1 tonne per day, with preference for 2 tonnes or more, and that they must be opened in sync with committed truck fleets so utilisation passes 50% quickly.

The principle mirrors strategies such as H2Accelerate, which also advocates building concentrated corridors first before attempting wider coverage, to ensure stations are full and viable rather than scattered and stranded.

The €8 test

The Alliance sets a firm “activation point” for hydrogen mobility at €8/kg at the nozzle, which it says is the point where hydrogen trucks can start competing with diesel on total cost of ownership.

In Germany, the parity point is even lower, closer to €6/kg, once new CO₂ pricing under ETS2 is included.

Current retail prices remain well above those levels, but GHMA says the pathway down is to build larger stations, increase throughput, and shift distribution towards liquid hydrogen supply chains.

Its modelling shows that moving a station from 30% to 60% utilisation can cut dispensed cost by around €3/kg, while scaling capacity from 1 tonne/day to 4 tonnes/day can shave another €0.5-1/kg.

Independent studies add context. The International Council on Clean Transportation, for example, estimates that break-even hydrogen prices for trucks in Europe sit in the €3.5-5/kg range depending on country and tax regimes – figures that assume heavy utilisation, low-cost supply, and consistent policy support.

By setting €8/kg as the activation threshold, GHMA is acknowledging that fleets won’t wait for perfect conditions, but they just need hydrogen to be close enough to diesel to get moving.

Use what’s available, clean it later

Another contentious point is the type of hydrogen allowed. Current EU support schemes often require renewable RFNBO “renewable fuels of non-biological origin” molecules, which GHMA says are scarce, expensive, and largely contracted to refineries under the RED3 scheme.

The Alliance argues that Europe should adopt the same approach it used for battery cars, which is – let vehicles and infrastructure scale first, then decarbonise the supply in parallel.

In its words, “deployment of hydrogen vehicles and refuelling infrastructure should be pursued independently of the decarbonisation of hydrogen molecule supply.”

That means allowing unabated, low-carbon and renewable hydrogen to activate the market now, with a mandated shift to fully clean hydrogen later.

GHMA points to Asia as evidence the model works. Korea, for instance, has around 40,000 hydrogen cars in operation, and China about 8,000 trucks and over 10,000 buses, while Europe remains stuck at demonstration scale despite twenty years of pilots.

The logic is that if BEVs were allowed to scale while grids were still fossil-heavy, hydrogen should not be held to a stricter standard.

A tilted field

The Alliance’s policy paper also highlights what it sees as structural bias towards batteries. It notes that the EU’s AFIR regulation sets an interim 2027 target for EV charging infrastructure but no equivalent for hydrogen until 2030, while tax rules treat hydrogen combustion engines differently from fuel cell vehicles, adding complexity and cost.

It also points to national schemes that bankroll motorway grid connections for chargers while hydrogen projects queue for permits, and to subsidy frameworks that demand renewable-only hydrogen even as battery cars have been allowed to charge from fossil-heavy grids without restriction.

“Today’s market activation efforts have failed,” the Alliance states, warning that Europe remains “locked in Phase 1” while other regions move ahead.

The result, it argues, is a retail business model that cannot work without repeated injections of capital, leaving OEMs reluctant to commit to volume production.

Industry’s ask

GHMA sets out a list of measures it says are needed to unlock the market. It wants hydrogen treated on equal terms with batteries in all relevant legislation – from CO₂ standards to Eurovignette toll exemptions – and it wants ecosystem incentives that fund fleets and stations together, guaranteeing station loadings of 50% or more from the outset. The Netherlands’ SWiM programme is cited as proof the model works.

It also calls for capacity payments – operational support for stations in low-demand areas until utilisation builds – echoing California’s approach, and it urges Member States to deliver toll exemptions and carbon pricing consistently, so operators can plan with certainty across borders.

The Alliance also points to tools like take-or-pay contracts and offtake agreements as ways to guarantee demand and reduce risk for operators investing in large-scale stations – mechanisms already familiar in the energy sector but largely absent in European mobility policy.

Above all, GHMA stresses the need for stability, arguing that uncertainty deters investment and that a predictable, harmonised framework would do more to unlock private capital than another round of fragmented subsidy.

The stakes for 2030

Truck makers, GHMA says, are willing to move if conditions improve. A 2024 survey of OEMs for Germany’s state-owned NOW programme suggested hydrogen could make up around 20% of new truck sales in Europe by 2030, and GHMA’s analysis shows fuel cell truck costs fall by about 60% once production scales into the tens of thousands per year.

But such scale will only be reached if fuel prices fall and stations are built to a standard that keeps operating costs down. Otherwise, hydrogen risks being left as a niche option while Asia and the US build volume.

There are also practical fleet considerations. Hydrogen trucks can refuel in minutes rather than hours, unlike the multi-megawatt charging times required for large BEV trucks, and they don’t lose as much payload to battery weight on long-haul routes – advantages that matter in the economics of freight.

Bottom line

GHMA’s central message is that Europe does not have a hydrogen technology problem – it has a throughput problem.

The trucks exist, the supply chain is ready, and the know-how is here, but without €8/kg fuel, stations built for trucks rather than cars, and a policy framework that doesn’t tilt the field against hydrogen, the economics won’t line up.

Its warning from Brussels is either Europe activates hydrogen trucks this decade, or it cedes the market to Asia and the US.

The strategy was presented at EU Hydrogen Week by Peter Mackey (Air Liquide), Manfred Schuckert (Daimler Truck), Jürgen Guldner (BMW), Niki Berger (Bosch) and Antoine Tournand (TotalEnergies), with Hydrogen Europe’s Jorgo Chatzimarkakis moderating.