Exclusive: “I don’t see batteries as the solution for electrifying the world,” says leading climate scientist, Carlos Duarte

In the soaring heat of the new Saudi Arabian city of Qiddiya, at the inaugural round of the FIA Extreme H World Cup, Driving Hydrogen’s Matt Lister sat down with Professor Carlos Duarte – Chief Scientist of Extreme H (the worlds first hydrogen powered motorsport event) – to discuss hydrogen’s role in decarbonising transport and why batteries may not be the answer.

“I’m a scientist working on marine science, water, and climate globally,” he begins. “I started working with motorsport in 2019, when Extreme E was first created. As a climate scientist, I was not too eager when I heard the word motorsport – burning fuel for fun and noise. But then Extreme E came with a very different proposition: to fast-track new technologies for sustainable fuels and silent mobility.”

He smiles. “So I was immediately on board.”

Five years later, that same experiment has evolved. “In marine organisms, larvae mature by metamorphosis into more capable creatures,” he says. “Extreme E is now undergoing a metamorphosis into Extreme H.”

From electricity to hydrogen

Why the shift? “The transition to a new energy system – both for powering our needs and for mobility – started with electricity,” Duarte says. “The next step is hydrogen.”

He explains it the way a biologist would. “Hydrogen is the currency of energy in nature. The procedure we use today to generate hydrogen from solar power is actually the same that was invented in nature about three billion years ago – photosynthesis.

“It’s splitting water to release hydrogen as a carrier of energy that then supports all of the energy requirements of the biosphere. So it’s only natural that we also use hydrogen.”

The by-product, he points out, is water – “a very clean technology which can actually be reutilised.”

He gestures toward the red-tinged Tuwaiq Mountains on the horizon. “There’s a reason they look orange,” he says. “That colour is oxidised iron – and it’s the fingerprint of orange hydrogen: hydrogen naturally produced underground by iron reacting with water.”

That, he says, could change everything. “In the last two years, the world has realised that there is a new form of hydrogen – orange hydrogen – that had not been mapped before.

It’s present in the biosphere everywhere, and the potential to harvest hydrogen directly from the ground, from the ocean, and from soils is huge. We might not need all of this artificial technology. We might just harness the hydrogen already being produced naturally.”

He believes the next revolution could come from geological hydrogen, drilled as cleanly as geothermal energy. “This country,” he says, glancing around the desert paddock, “is going to play a major role – repurposing drilling technologies to extract hydrogen from the land and ocean.”

The evolution of hydrogen mobility

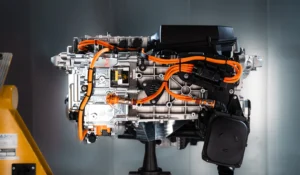

The hydrogen fuel cell technology itself inside the cars, Duarte says, is already proving viable. “The Toyota Mirai was released about 13 or 14 years ago. A few were sold, but production stopped because there wasn’t enough infrastructure or hydrogen supply. Toyota felt it wasn’t the time. But now it’s producing Mirais at scale.”

The challenge now is global transport – “how to move hydrogen across the world.”

Because hydrogen is light, he explains, “you need to use another carrier with higher energy density.” He points to ammonia and methanol as the main contenders. “Ammonia can be produced by coupling hydrogen with the Haber-Bosch process, the same reaction used to make fertiliser.

“The infrastructure is already there, but we must be careful with leakage – ammonia released to the environment can create problems in aquatic systems, and nitrous oxide is a powerful greenhouse gas.”

Researchers at Duarte’s own King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) have published new methods for oxidising ammonia back to nitrogen gas safely. “We’re progressing,” he says. “Methanol also has potential but needs careful management because it’s a volatile compound with a high greenhouse gas potential if released.”

Meanwhile, real-world hydrogen transport is already taking shape on the high seas. “The first large hydrogen-fuel-cell vessel was launched in April – a 200-metre ship from MSC’s Explora line,” he says.

“I was on board the first vessel that operated with green ammonia, and there’s already one much larger that works with hydrogen fuel cells. So hydrogen is becoming an option for large lorries, ships, and soon, aviation.”

Batteries and the limits of electrification

I ask the Professor about the role of hydrogen compared to batteries, and why make hydrogen when you can electrify directly, but Duarte doesn’t hesitate in his response. “I don’t see batteries as the solution for electrifying the world,” he says.

“The first challenge is sourcing and disposing of the materials in a way that doesn’t impact the world. Mining affects ecosystems. Now we’re looking at doing deep-sea mining to source metals for batteries – and many countries think there should be a moratorium because of the unknown impacts on the deep sea.”

He points to the Atacama Desert, where Extreme E raced last year. “It’s part of the Lithium Triangle – Argentina, Chile, and Bolivia – which provides about one-third of the world’s lithium. Extracting lithium from these vulnerable ecosystems creates serious impacts. Even flamingos are affected, because they live in the same habitats where lithium is being extracted.”

Then there’s the waste problem. “The world is committed to 30 million tonnes of battery waste by the end of 2030 that we don’t know how to recycle,” he says. “One method is melting them at very high temperatures, generating toxic fumes. The other is acid dissolution, which produces toxic waste.”

He pauses. “Hydrogen is free of all of those elements of pollution. The outcome of running hydrogen cars is water.”

The weight problem

Metal-based batteries, he says, have another drawback: density. “The Odyssey 21 vehicles used in Extreme E carried about 700 kilograms of batteries,” he says. “You carry a lot of weight, and that limits range. It’s one reason the new hydrogen-powered Pioneer 25s feel so different to drive.”

He adds that limited range is one of the biggest barriers to adoption – especially in countries like the United States, “where distances are very large.”

And weight, again, has environmental consequences. “We’ve learned that tyres are a major source of microplastics,” he says. “Once we had the tools to measure nanoplastics – only about three years ago – we realised the main source was tyre wear. Those particles go into our lungs, our blood, and even our brains.”

One of Extreme E’s historic partners, Continental, responded by developing tyres with more sustainable materials. “They replaced plastic polymers with organics – rice-husk silica, recycled PET, and even latex from dandelions,” Duarte says. “By the last season, around 40% of the tyre mass was non-plastic, and their goal is to reach 100%. Extreme E was a driver of that transition, and those tyres are now moving into commercial vehicles.”

It should be noted, however, that whilst this weight issue is true as a theory – the Pioneer 25 hydrogen race cars here at Extreme H are heavier than their Extreme E predecessors. But they are also larger, meaning more material used in their construction.

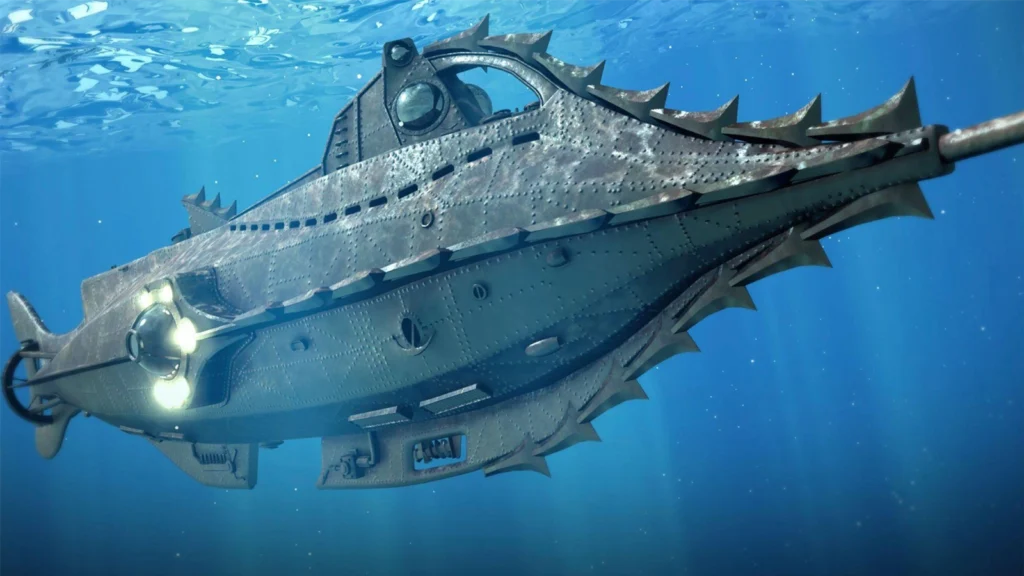

Nautilus, Verne, and the long arc of hydrogen

Hydrogen, Duarte notes, isn’t a futuristic concept – it’s an old one finally being realised. “Batteries were invented by Volta in the late 18th century,” he says, “but hydrogen as an energy carrier has taken much longer to develop because it required major advances in chemistry and engineering.”

He smiles. “In Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, the submarine Nautilus was powered by electricity – and that electricity was generated by hydrogen produced from the hydrolysis of seawater. Verne imagined that more than a century ago. And that exact technology has now been invented – just two years ago.”

It’s a reminder, he says, that “electricity has been with us for a long time, but hydrogen is only now becoming a reality.”

Sport as catalyst

Extreme H, Duarte says, is “an ecosystem that catalyses technology development and partnerships through something that’s fun and exciting – sport.”

He’s come to see racing as a communication tool. “Sport is the big unifier,” he says. “It crosses borders and reaches the world beyond the bubble of sustainability. People who don’t usually read about climate change are learning about the future of fuels and mobility.”

That, he believes, is how change starts – not with policy papers, but with visibility. “Extreme E was about raising awareness,” he says. “Extreme H is about technology. It’s showing what the hydrogen future actually looks like.”

The next phase

Asked whether hydrogen will replace batteries or complement them, Duarte is unequivocal. “I don’t see batteries as the solution for electrifying the world,” he says again. “We can’t mine and dispose of the materials without damaging the planet, and deep-sea mining will only make it worse.”

There are alternative chemistries – “graphene-based batteries and organic batteries,” he says – but they’re not ready. “Graphene isn’t yet scalable at cost, and while organic batteries are viable and fully recyclable, they need major funding to improve performance.”

For now, hydrogen feels like the simpler, more natural answer. “It uses what nature already made, moves energy cleanly, and turns back into water when it’s done.”

As the Pioneer 25s return from their runs – hissing, clicking, and venting water vapour into the desert air – Duarte watches them quietly.

“Hydrogen,” he says, “is the currency of energy.”