Exclusive interview: BMW’s Dr. Jürgen Guldner on hydrogen cars, infrastructure and why 2028 is the moment

Driving Hydrogen sat down – quite literally, in Munich traffic – with Dr. Jürgen Guldner, General Program Manager Hydrogen Technology at BMW, for a ride in one of BMW’s iX5 Hydrogen models.

This small pilot fleet is the culmination of more than four decades of hydrogen development at BMW, and is the prelude to something bigger – a full on hydrogen production X5 car coming in 2028.

Over the course of an hour weaving past buses, junctions, cyclists and the BMW Museum, we talked through the car itself, the technology behind it, the perennial question of infrastructure, and why BMW insists hydrogen must sit alongside batteries – not instead of them.

A familiar car, with a very different heart

“The car we’re driving here today is based on our production X5 model. We basically took out the powertrain and put a hydrogen powertrain in it,” Guldner explained as we rolled along.

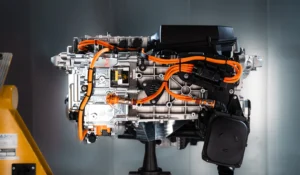

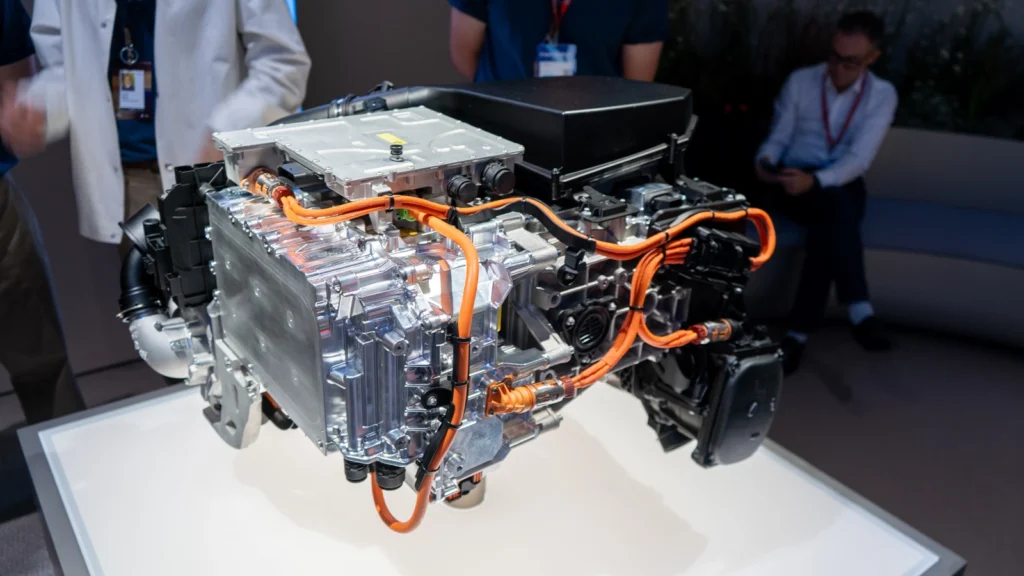

The setup is surprisingly straightforward once you break it down. There’s a fuel cell stack under the bonnet, two hydrogen tanks – one squeezed into the middle of the chassis between the seats and another tucked under the rear – and a compact but high-power buffer battery.

“It has 170 kilowatts of electric power. Very little energy is stored in the battery because the hydrogen stores the energy, but it adds great acceleration, as you know from BMWs, and it helps to regenerate energy when braking.”

That energy goes through the same rear-mounted electric motor found in the BMW iX battery SUV. “The fuel cell generates electricity, the battery adds dynamic power, and you get that instantaneous response from your right foot,” he said.

Even when stationary in traffic, the system has been designed to behave more like a generator than a traditional engine. “The fuel cell actually turns off when you’re sitting, like right now,” Guldner pointed out, gesturing at the stop-start Munich lights.

“It ramps up with the dynamics of your right foot. That was special BMW engineering – you press the pedal and feel how the battery and fuel cell power come together.”

How does a hydrogen car work

From a chemistry perspective, what’s happening inside the stack can sound almost disarmingly simple. In effect: hydrogen plus oxygen equals water.

“Basically the end product of the reaction is water,” Guldner said. “At the catalyst, the hydrogen molecules give up their electrons. The electrons drive the car, they come back on the other side of the fuel cell where there’s a membrane in between.

“They meet the oxygen, ionize it, and then the oxygen takes on the hydrogen proton. It’s a very controlled reaction – instantaneous, distributed across the cell, and that’s why the dynamics are so good.”

In reality, achieving that level of control and reliability takes serious engineering. Do it badly and you have an, err… chemistry experiment. Do it well and you have a car that drives like a BMW.

…or a Toyota – considering that’s where BMW has sourced the fuel cell stack from. Though I hasten to add, that is no bad thing, because being from Toyota, it will always work.

Every kilogram of hydrogen consumed produces about nine litres of water – mostly as vapour, mixing invisibly with the exhaust plume of traffic around us. With a kilogram good for roughly 100 km of driving, the car leaves little behind but a damp patch.

Safety first, before the first drive

If you were to mention “hydrogen” in the street, the word can often conjure up the mental image of Hindenburg, or… other such explosive devices. BMW knows it has to address that head-on, and the Dr. reassures me the cars are safe.

“Hydrogen cars are safe. Safety first, same standards as all other cars,” Guldner said. The pilot fleet went through crash tests and even fire tests before anyone drove one on the road. “We had a first batch of cars made just for safety testing,” he said. “Then we built a second batch for driving development.”

The carbon-fibre reinforced tanks are certified to international standards and designed to take serious punishment. “Hydrogen cars are as safe as natural gas cars, and there are already many of those out there,” he added.

Why fuel cell, not combustion?

BMW has tested both fuel cells and hydrogen combustion engines throughout the years, testing both liquid hydrogen and gaseous hydrogen as fuels.

The company’s 7-Series hydrogen saloon of the 2000s famously ran on liquid hydrogen, stored in a cryogenic tank that slowly evaporated the fuel away if you left it parked too long.

“This car has 500 kilometres of range. With a combustion engine we would only get 300,” Guldner explained. “The fuel cell is more efficient because it directly produces electricity to drive the car. So we think for passenger vehicles the fuel cell is the way to go.”

Liquid hydrogen still has a future, he pointed out, but not in passenger cars. “Liquid is good for transporting hydrogen over long distances – from Saudi Arabia, Australia, Japan, Korea. But in a passenger car, where it may sit unused, gaseous hydrogen at 700 bar is the worldwide standard.”

That standardisation has been stress-tested. “We went to over 20 countries with one car, one nozzle, and we could refuel everywhere,” he said with a shrug, confirming that part of the puzzle is already solved.

Forklifts, trucks and productivity

Our route took us past Munich’s northern suburbs and into the shadow of BMW’s Leipzig plant conversation. Here, Guldner revealed, hydrogen isn’t confined to vehicles on the road.

“We also have hydrogen fuel cells in our production for the forklifts,” he said. “The plant in Leipzig is the pilot here. They’re converting battery forklifts into hydrogen simply because it’s better operationally. The worker drives to a station, refuels in a minute, and keeps going.”

It’s the same story with logistics trucks. “They have to be on time, just-in-sequence deliveries. They don’t have time to charge. For longer distances, we definitely see hydrogen as the answer.”

That productivity advantage matters far beyond BMW. I pointed out that in the UK, logistics operators can wait more than a decade just to get a grid connection big enough to charge heavy trucks, while AI data centres, for instance, are allowed to jump the queue. Guldner nodded. “That will be the key that unlocks the hydrogen ecosystem,” he said.

Why 2028 is not 2005 all over again

I’d been digging through BMW’s archives the night before, and came across a press release from around the year 2000 confidently predicting a hydrogen filling station near every branch by 2005 and a nationwide network in Germany by 2010. None of it ever arrived. So I asked Jürgen why – this time – it would be different.

“Back then, hydrogen was only considered for passenger cars,” he said. “Now it’s part of the energy transition as a whole. The International Energy Agency said in 2019: we need molecules as well as electrons.”

That wider role changes everything. Europe’s planned “hydrogen backbone” will repurpose natural gas pipelines to transport hydrogen, linking major producers with industries like steel, chemicals and fertilisers. At the same time, large-scale production is being planned for shipping and imports.

On the ground, trucks and buses provide the commercial pull that was missing 20 years ago. “They provide much higher offtake at stations. They operate every day. That makes stations viable,” he said. Passenger cars then simply share the network.

It’s a neat way of trying to sort out the chicken-and-egg dilemma. Stations get the daily throughput from heavy vehicles, and private cars can piggyback from the same pump.

Hydrogen vs. battery electric

BMW insists this isn’t about undermining its newly launched Neue Klasse battery EVs, it’s all about offering choice to the customer.

“We get feedback from people who would love to drive a zero-emission vehicle but a battery car doesn’t fit into their daily life. Hydrogen can be the solution,” Guldner said. “It’s not competition of technologies. It’s about offering the right mobility choice.”

I mentioned the towing example – unhooking a trailer at a motorway charging bay just to plug in – and he laughed. “Exactly. That’s where a hydrogen car can be the more convenient choice.”

Even the economics can add up. “It sounds counterintuitive, but the electric charging network gets more expensive the more you build of it,” Guldner said.

“At some point you have to upgrade the grid behind it – bigger cables, transformer stations. With hydrogen, you can integrate into an existing fuelling station. The combination will be cheaper.”

Europe’s industrial advantage

There’s also an industrial and geopolitical logic to BMW’s – and the wider European automakers – resurgence in hydrogen.

“Another nice thing about hydrogen fuel cells is that they can reuse a lot of the industry that we have for combustion engines,” Guldner explained.

“Sensors, valves, compressors, cooling pumps – these are all things the automotive industry knows well. We can reuse machines, workforce, engineering. It’s a value chain we have here in Europe.”

That matters against a backdrop of battery supply chains dominated by Asia. “Having a second leg to walk on is a good thing, rather than putting all eggs into one basket,” he said.

Car-making makes up about 8% of Europe’s manufacturing GDP, and supports a huge tier-one and tier-two supply chain. Hydrogen offers a way to protect that base, as opposed to hollowing it out as, unfortunately, the current trajectory is doing.

AFIR and the roadmap to 2030

As we edged past a lumbering diesel bus, I asked whether hydrogen could end up as diesel’s natural successor. He liked the analogy. “I think the duality is similar. Nobody worries about petrol and diesel existing side by side. In the future we’ll have battery electric and hydrogen in parallel. It depends on the use case.”

Europe’s AFIR regulation will help too. It requires hydrogen stations to be built every 200 km on the major European road network by 2030, plus in every “urban node” – essentially every big town.

“That’s just around the corner,” Guldner said. “Highway stations will need one-ton daily capacity, which is only a few trucks a day. We already see those stations being built. And once they are, networks can spread.”

2028 is the date in the diary

BMW has confirmed it will launch a production hydrogen model in 2028. The exact model was still under wraps at the time.

“We’re in the final stages of decision-making,” Guldner said with a half-smile. “Within this year we’ll know roughly what it will be.”

Since our day in Munich, however, BMW have revealed that the model will in fact be an X5, offering the choice of five powertrains within one model from 2028.

The verdict, from behind the wheel

As we pulled back into BMW Welt, past the sweeping curves of the company’s museum and headquarters, the conversation circled back to the basics.

“A hydrogen car combines the use case of a gasoline car with the features of electric,” Guldner said. “You drive to a station, fill up in minutes, and drive with great dynamics. The output is water. It’s very clean. The technology is mature. Now it’s about scaling.”

BMW thinks the “timing is right” and the moment to scale is 2028.