Exclusive: How the FIA tested hydrogen to destruction – and it passed

When the FIA agrees to put its name to something, it doesn’t do so on a whim. Especially not when that something involves racing cars powered by a gas under seven hundred times atmospheric pressure.

The folks in Paris are methodical, cautious, and sometimes frustratingly pedantic – but with good reason. The rule book in motorsport is written in hindsight, and often in blood. So when hydrogen turned up at their door, it wasn’t a question of excitement. It was a question of proof.

The world’s first hydrogen-powered racing series, FIA Extreme H World Cup, had to be shown to be safe, serviceable, and competitive under the same conditions as any other form of motorsport.

The Pioneer 25, designed and built by race car boffins, Spark Racing Technology, became the laboratory on wheels through which that proof would come.

And the man charged with making it work was Mark Grain – former McLaren F1 Chief Mechanic turned hydrogen anorak – now the technical boss at Extreme H. For two years, his job was to turn curiosity into certification, and ideas into something that could survive being driven flat-out in the sweltering deserts of Saudi Arabia.

“It was all centred around homologation,” says Grain. “Crash tests, impact tests, the survival cell, the hydrogen system – everything had to be validated. That was the biggest part of the job.”

Testing hydrogen for the first time

Because hydrogen had never been raced under FIA rules before, there wasn’t much – if any – precedent. Electric powertrains had already gone through the wringer with Formula E and Extreme E, but compressed gas – particularly one this volatile – demanded a new playbook.

A joint testing programme was drawn up between Spark, the FIA’s safety department and Grain’s engineering team. The brief was simple enough on paper – to prove that a flammable gas at 250 bar could be made as safe as petrol, and more stable than lithium-ion batteries, in a crash.

“Certainly for FIA it’s a milestone,” said FIA Technical Delegate Laurent Arnaud. “It’s FIA’s first ever hydrogen-powered competition. So we are super proud. But it’s clear that it has been hard work for the whole year to get to where we are today.”

He added: “When it was decided to follow this project, we developed a kind of full matrix – you cannot imagine how big it was. We try to achieve this kind of category according to this type of competition, but for the future we are always learning, always trying to develop, to elaborate new practices.”

The tests were physical, violent, and nerve-racking to watch. The sled test, for instance, involves a fully pressurised Pioneer 25 race car being smashed into a wall at 45 km/h to assess structural integrity.

The rock test used a pyramidal steel impactor driven into the car’s belly – the sort of hit you’d expect if a driver got it wrong and landed badly off a jump.

“We didn’t even get close to breaching them,” says Grain. “The tanks are massively over-engineered. You can fire high-calibre rifle rounds at them and they won’t penetrate. I’ve seen it done.”

A network of solenoid valves isolates the system within milliseconds if a pressure drop is detected, while a visual warning light alerts marshals in the event of a leak.

“Hydrogen wrongly comes with preconceptions,” Grain says. “People still think of the Hindenburg, but that was a hundred years ago and it wasn’t even the hydrogen burning – it was the balloon fabric. In a crash, you’d rather be in a Pioneer 25, where the hydrogen just dissipates, than sitting over a pool of petrol.”

The FIA oversaw every stage, cross-checking data thoroughly and growing the knowledge base.

“In terms of safety tests, what we have done with this car – if you do that with a normal road car, none will pass that,” said the FIA delegate.

“And in terms of hydrogen, this is something unbelievable. Always safety on top of everything, on top of each question. If everything goes well, nobody takes care, but if something happens, that’s why you need to put in place a very strict and strong test.”

That sign-off made history – the first time hydrogen propulsion had ever been formally homologated for use in an FIA World Cup.

From crash tests to competition

The testing had proven the numbers, but racing is never a laboratory exercise. The real examination came in Qiddiya, a stretch of Saudi desert where temperatures touched 40 °C and sand infiltrated everything from the suspension wishbones to the circuit laptops.

“Coming out here with 38 or 39 degrees ambient was a journey into the unknown,” Grain says. “You get vibration frequencies you don’t see in Europe. We had a few sensor issues, nothing major. Spark and the teams reacted quickly – new software overnight, calibration tweaks in the morning. That’s racing engineering.”

Eight teams, sixteen drivers, and no hydrogen-related issues. The systems ran as designed, the tanks held their pressure, the fuel cells performed, and the FIA’s observers had nothing serious to note – which, in their world, is a good day.

“The trend’s always been upward,” Grain says. “No setbacks that have really held us back.”

It was the first time hydrogen had been raced, refuelled and serviced under full FIA regulation.

“This weekend has been very good,” the FIA technical team said. “We’ve managed, between promoter and our side, to have a good collaboration all over these two weeks.

“We see some things that we would like to improve directly. The promoter also has seen the same. This weekend will become part of the 2026 regulation.”

The car itself

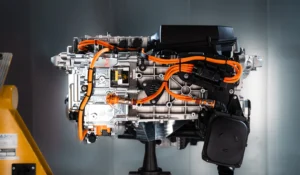

Beneath the surface, the Pioneer 25 is an impressive bit of engineering. Power comes from a Symbio fuel-cell stack feeding a 36 kWh battery and twin 200 kW motors, delivering a combined 400 kW (550 bhp). It’s no flyweight at 2.2 tonnes, but it’ll hit 100 km/h in 4.5 seconds and climb a 130% gradient without much struggle.

“In the old Extreme E car you’d turn in and lift an inside wheel,” Grain explains. “Now all four stay on the ground. It’s gone from being an engineering exercise to a driver’s competition.”

The difference is down to new suspension geometry and Fox Live Valve dampers, which continuously adjust damping rates to terrain. The result isn’t just faster lap times – it’s a car that drivers can trust and that engineers can measure.

“Give racing drivers adjustability and toys,” Grain laughs, “and they’ll use them. They’ll absolutely use them.”

Changing minds with data

For the FIA, the biggest win wasn’t the spectacle but in the numbers. The homologation data, the telemetry, the post-race data – it all of it adds up to a working model of how hydrogen behaves in competition. It’s evidence that can be used, replicated, and improved.

“Inside the FIA technical department there is a kind of research and development group which are looking at all types of energy and hydrogen is part of that,” the FIA official explained.

“We’re working with big OEMs to try to find the best way we can introduce and put in place hydrogen.”

Extreme H has also given engineers and race crews something that can’t be modelled – experience. Handling high pressure hydrogen in the heat of a live race weekend has turned theory into practice.

“This is Genesis,” says Grain. “The car’s first competitive outing. We’ll go through all the race data, all the feedback, and keep pushing. The car’s light, agile, and there’s a lot more to come.”

He’s quietly pragmatic about what it all means. “It’s not the only solution, but it’s a good one,” he says. “Motorsport’s always accelerated technology. Formula E started with drivers swapping cars mid-race. Look where that is now. We want to do the same for hydrogen.”