JCB’s hydrogen digger gets to work on the Lower Thames Crossing

A British-built JCB hydrogen excavator has been put to work in Kent – the first time anywhere in the world that a hydrogen-powered construction machine has been used on a live site.

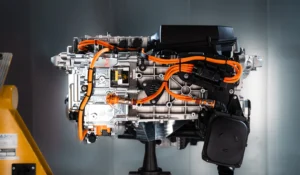

The 20-tonne 220X excavator (a digger to you and me), powered by JCB’s own hydrogen combustion engine, is being used by Skanska on National Highways’ Lower Thames Crossing project. Hydrogen is being supplied by Jo Bamford-owned Ryze, with the machine itself being operated through Flannery Plant Hire.

First real-world use

After a £100 million investment in hydrogen engines by JCB, the hydrogen prototypes have been through many months of controlled testing, but this is the first time one has actually been put to work properly – carrying out ground investigation surveys near Gravesend as part of early works on the Lower Thames Crossing.

Skanska’s project director Chris Ottley said the digger had “proved that the hydrogen machine is a capable replacement for diesel-powered machinery.”

According to National Highways, the trial has already saved over a tonne of CO₂ equivalent during its first four weeks of operation. Straight into the record books then.

Building Britain’s greenest road

The Lower Thames Crossing will link Kent and Essex via a new road and twin-bore tunnel, doubling capacity across the Thames and providing a new freight route between the South East, Midlands and North.

National Highways says it will also be the UK’s first carbon-neutral infrastructure programme – eliminating diesel from all worksites by 2027 through a mix of hydrogen, electric and biofuel power.

A contract for the project’s hydrogen supply and distribution – expected to be the largest of its kind in UK construction – is due to be awarded later this year.

By the time construction begins in 2026, National Highways wants every worksite on the £10 billion scheme to be running on “low-carbon machinery”.

The project’s sustainability plan also includes a million new trees, two new parks, seven wildlife bridges and 40 miles of walking and cycling paths – six times more green space than road.

Industry reaction

The Civil Engineering Contractors Association (CECA), representing over 300 UK contractors, described the deployment as a milestone for decarbonising construction.

Ben Goodwin, CECA’s Director of Policy and Public Affairs, said it shows the industry is “moving from pilots to real-world decarbonisation on site,” but added that contractors now need “clear and consistent safety standards, reliable refuelling and commercial models that reward emissions reduction without pushing unmanageable risk down the supply chain.”

JCB’s Steve Fox called the trial “a huge milestone for the construction industry,” saying hydrogen had “proven its worth on site as a carbon-neutral fuel in a working JCB construction machine.”

From quarry to construction site

The Gravesend deployment follows an earlier trial at Gallagher’s Hermitage Quarry, where JCB’s prototype underwent its first live evaluation. Full production of hydrogen-powered excavators is set to begin at the company’s Rocester factory in 2026.

Roads and Buses Minister Simon Lightwood said the Lower Thames Crossing “shows major infrastructure can be delivered hand in hand with environmental targets,” while National Highways’ Matt Palmer said it proves “the British construction industry has the vision and skills to build the projects needed to drive growth in a way that enhances the environment.”

Hydrogen plant remains rare on construction sites, but the Lower Thames Crossing could change that.

If it succeeds in cutting out diesel entirely by 2027, it will set a powerful precedent – and show that hydrogen machinery isn’t a concept anymore, but a working tool on Britain’s biggest building project.