Hydrogen engines could be Britain’s ace up its sleeve – if ministers don’t strangle them

A new APC report says hydrogen ICE could protect UK jobs and clean up heavy transport. But policy might kill it before it starts.

The UK has a habit of backing the right technology at the wrong time – or smothering it before it has a chance to breathe…

According to the latest report from the UK’s Advanced Propulsion Centre, hydrogen internal combustion engines (H2 ICEs) may be next in line.

The report argues that H2 ICE offers a viable, low-emissions option for decarbonising trucks, buses and off-highway machinery – and a chance to repurpose the UK’s existing ICE supply chain.

But unless policymakers act fast, rigid “zero tailpipe” rules could block it from domestic roads entirely.

Hydrogen engines are ready to go – and Britain already knows how to build them

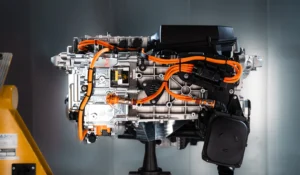

Hydrogen combustion works now, and the UK already has the skills and supply chain to deliver it.

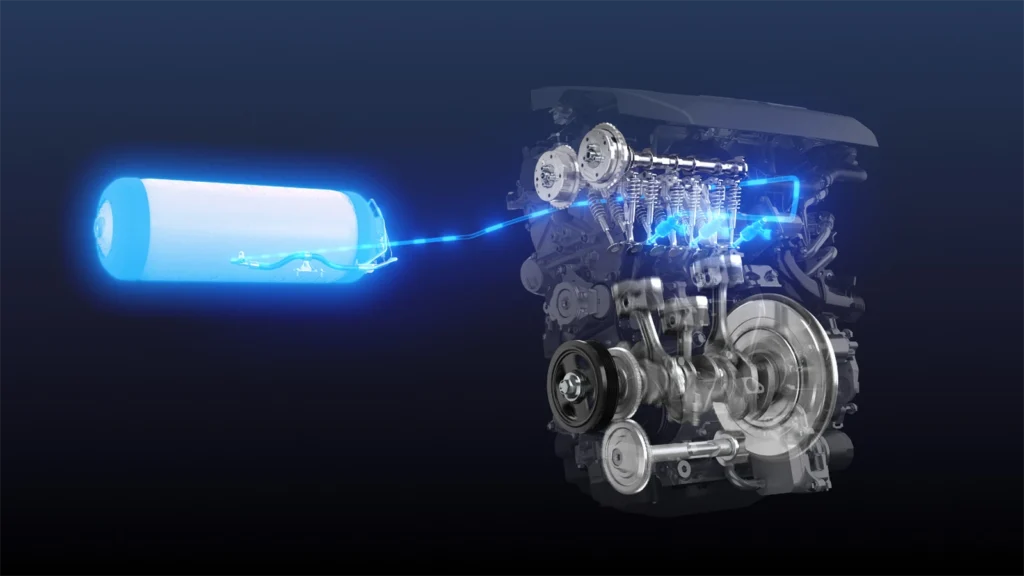

The APC points out that hydrogen ICEs deliver 99.95% less CO₂ than today’s ‘Stage V’ diesel engines, and emit only trace levels of NOx – well within Brussels’ upcoming Euro 7 limits.

These engines run leaner than petrol, often using turbochargers or superchargers to maintain output, and they closely resemble existing diesel designs.

That means British manufacturers can repurpose existing tools, parts and expertise – cutting cost and complexity.

“The UK already boasts a robust ICE supply chain and deep-rooted engine expertise,” the report says.

With the right support, firms could adapt their current diesel engine designs to run on hydrogen – no need to retool entire factories.

Off-highway machines need something rugged – hydrogen ICE fits the bill

Some use cases make battery-electric or fuel cell vehicles a poor fit, i.e construction machinery, agricultural vehicles and non-road equipment.

These machines work in harsh, dusty, unpredictable conditions. Hydrogen combustion just copes better.

The report flags that hydrogen fuel-cell drivetrains need clean air, stable cooling, and more sensitive electronics – great for on-road – but all of which struggle in the rough-and-tumble world of off-highway work.

In contrast, hydrogen ICEs tolerate dirt, heat and vibration. They also allow operators to retain existing drivetrains and cooling systems, which makes retrofits easier and downtime shorter.

In other words, hydrogen combustion lets you decarbonise the digger without throwing away the machine.

Fuel cells work best in structured fleets – but not everywhere

Fuel cells definitely aren’t redundant. They’re just better suited to specific roles – like return-to-base fleets, long-haul trucks, and urban buses.

In those cases, where operators have access to depot-based fuelling and predictable routes, FCEVs deliver fast refuelling, long range and quiet, zero-emissions performance.

But the APC stresses that BEVs and fuel cells alone can’t serve the entire market – especially not in the sectors where payload matters and off-grid operation is the norm.

Instead of backing one horse, the report says, the UK should match propulsion type to application – and hydrogen ICE is what fits best for the dirtiest jobs.

UK regulations risk killing hydrogen combustion before it starts

While hydrogen ICE could work technically, the UK’s current policy might rule it out legally.

The UK has committed to zero-emissions-at-tailpipe rules for new trucks by 2035. Under that framework, even an engine that emits 0.01 grams of NOₓ could be locked out – despite reducing overall CO2 by near-as-dammit 100%.

The EU takes a more flexible approach. Its Euro 7 proposals aim for a 90% reduction in CO2 by 2040 and consider whole-vehicle emissions, including aerodynamics, tyre wear and energy source.

That opens the door for hydrogen ICEs to play a role in reducing total emissions, even if they aren’t tailpipe-zero.

If the UK holds firm on tailpipe purity, it risks excluding hydrogen combustion from its own roads – while other countries adopt and export it.

Britain could develop hydrogen ICE – for everyone but itself

That policy gap creates a bitter irony. The UK could become a global hub for hydrogen ICE production – but only for export.

The APC report calls out that risk directly. With British expertise in combustion engines, and strong demand for transition technologies in global markets, the UK is well-positioned to lead in hydrogen ICE development.

But unless it aligns its regulations with the reality of how decarbonisation works in practice, it could lock that technology out of domestic use.

Worse still, it could send those jobs and factories overseas.

Infrastructure is still lagging – especially for long-haul

Even if the engines are ready, vehicles still need places to refuel, and at present, the UK lacks a joined-up hydrogen infrastructure.

Most hydrogen trucks and buses today rely on private depot fuelling, which works fine for fixed-route fleets but falls apart for long-haul or cross-border operations.

Without public hydrogen stations, operators may be forced to offload goods mid-route onto diesel trucks or split payloads to avoid weight limits.

The report makes clear: FCEVs and H2 ICEs offer better payload efficiency than BEVs, but only if there’s somewhere to refuel them.

A flexible strategy needs flexible tools

The APC asks the government simply, to keep options open.

Hydrogen combustion is clean, cost-effective, and compatible with the UK’s manufacturing base.

Fuel cells are efficient, scalable, and ideal for fixed routes. Each solves a different problem. The real risk lies in backing one to the exclusion of the other.

If the UK wants to lead the hydrogen mobility space – and protect the industries it already has – it needs to make space for both.

Otherwise, we’ll keep designing brilliant hydrogen engines that drive innovation, investment, and climate wins… for everyone but us.