Analysis | Europe’s €5 trillion mistake: Why a battery-only future risks gridlock – and insolvency

Scroll through LinkedIn or stroll round any industry expo and you’ll hear the same binary soundtrack: batteries good, hydrogen bad (or vice-versa).

Entire marketing budgets are spent framing the future of transport as a winner-takes-all grudge match.

Meanwhile, the scoreboard that matters tells a different story.

Electrically chargeable cars did steal one-fifth of EU new-car sales last year, yet 96% of the vehicles actually on the road still gulp petrol or diesel.

The task, bluntly, is to swap out the other 240-odd million fossil burners before climate deadlines turn into climate fines – and to do that without detonating the Treasury, the power grid or the periodic table.

Now this is not about cheering one technology from the terraces, but about making sure Europe can afford to actually finish the job.

As the numbers below should make painfully clear, a single-track solution piles unmanageable costs and supply-chain risks onto an already creaking system.

Run the sums honestly and the conclusion is a dull but decisive one: batteries AND hydrogen, side by side, get us there faster, cheaper and with a lot less drama.

With that context set, let’s follow the money, the metals and the megawatts.

The size of the hill we still have to climb

Electrically chargeable vehicles (BEVs and PHEVs) grabbed 20.8% of EU new-car registrations in 2024 – but they still represent only 3.9% of the 249 million cars circulating today.

Put differently, 96% of Europe’s light-duty fleet remains resolutely fossil-fuelled. Turning that super-tanker around takes a multi-technology toolkit, not a single silver bullet.

Carbon scorecards: a near draw when you count from mine to scrapyard

A cradle-to-grave assessment for the Hydrogen Council shows that, once you include vehicle manufacture, recycling, infrastructure, and the carbon intensity of the energy itself, BEVs and FCEVs land in broadly the same life-cycle CO₂ band.

The swing factor is the cleanliness of the electricity or hydrogen supply – NOT the drivetrain.

For instance, plug a BEV into Poland’s coal-heavy grid at 6pm and it can out-pollute a hydrogen Mirai tanked with offshore-wind hydrogen at 3am.

Conversely, France’s nuclear-heavy electrons make most hydrogen pathways look grubby. Decarbonising energy, not sparring over propulsion, is where the big gains lie.

Following the money: €3-5 trillion nobody needs to spend

McKinsey’s cost model for the Clean Hydrogen Partnership ran a brutal thought experiment, which is: what if every European road vehicle had to be battery-electric?

The answer is eye-watering. They calculated a €3-5 trillion premium in extra grid capacity and charging hardware by 2050, versus a scenario where just 10% of vehicles use hydrogen.

It’s the peaks that do the damage. Holiday-Friday traffic, Amazon Prime Day delivery spikes, 3am fridge trucks at wholesale markets – all would demand simultaneous megawatt-class charging if batteries alone did the work.

Add a 1-tonne-per-day hydrogen dispenser to the same forecourt and those peaks flatten, along with the budget.

Grid reality check: the Netherlands as early warning

Europe’s most electrified nation is already flashing red. Zuid-Holland became the last Dutch province to run out of high-voltage headroom in late 2024, with around 70 GW of projects now sitting in a connection queue that stretches to the 2030s.

The system operator’s stop-gap – off-peak-only contracts – liberates just 9 GW of slack.

Electrolysers, by contrast, can soak up those night-time electrons, stash the energy as molecules and truck it to filling stations when the grid is asleep.

Peaks are what break networks, and hydrogen shaves those peaks.

Digging up the planet: raw-material roulette

Even after every announced European mine, refinery and recycling plant comes online, the EU will cover only about 16% of its nickel and 9% of its cobalt needs in 2030.

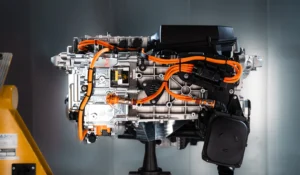

Batteries use those metals by the tonne; fuel-cells need grams of platinum and iridium – much of which can be recycled from yesterday’s diesel catalytic converters.

Running two drivetrains in parallel flattens geopolitical risk instead of concentrating it in whichever country controls tomorrow’s lithium triangle.

The key supplier of which is Europe’s strategic trading adversary – China.

Where each technology actually wins

| Segment | Batteries shine when… | Hydrogen shines when… |

| Urban delivery & commuters | Daily range: up to 200 km; overnight charging; strong grid | – |

| Taxis, ride-hail, emergency vehicles | – | Cars work 24/7; 3-minute refuel keeps wheels turning |

| City & peri-urban buses | Depot charging fits shift patterns | Hills, heaters, 18-hour duty cycles, grid-weak depots |

| Long-haul HGVs | Range fits legal rest breaks and truck stops have 3-10 MW spare | 1,000 km stages; <15 min refuel; full payload retained |

Take buses for instance. EU modelling shows half of scheduled mileage will still be “challenging” for batteries by 2030, and a third even in 2050 – unless operators buy spare vehicles or rewrite timetables.

Cologne’s 100-plus fuel-cell fleet, by contrast, runs familiar routes with ten-minute refuels and no extra kit.

Trucks: the 350 TWh elephant in the lay-by

Daimler Truck’s CTO, Dr Andreas Gorbach, puts numbers on the whiteboard – convert Europe’s six million trucks to batteries and you need about 350TWh of extra green electricity each year- – that’s roughly three-quarters of Germany’s entire annual demand.

Every motorway rest area would become a sub-station. Hydrogen refuelling stations cost money, but they don’t require a 20-MW feed every 80km, and they preserve the eighth pallet row that a five-tonne battery pack would displace.

Policy is already hedging its bets

Brussels seldom admits it, but the rulebook has quietly gone dual-track.

Its Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation mandates a public hydrogen station every 200 km on the TEN-T core network – and one tonne of H₂ per day in every ‘urban node’ – by 2030.

Heavy-duty CO₂ standards tighten to -90% by 2040, while urban buses must be 100% zero-emission by 2035.

Subsidy darts now land on both charging hubs and hydrogen corridors. The blended roadmap is already baked in.

Who pays the first bar tab?

Capex grants pour concrete, yet early utilisation can be brutal. The Dutch SWiM scheme tackles that chicken-and-egg by covering part of the operating cost for both pumps and vehicles until traffic grows.

Brussels’ forthcoming Sustainable Transport Investment Plan aims to copy-paste the idea across the bloc, while the European Hydrogen Bank underwrites offtake risk for early green-hydrogen producers.

None of this favours one tech over the other, it just simply accelerates zero-emission kilometres while private finance digests the business case.

The destination

Europe can decarbonise the hard way – oversize every cable, pray the cobalt turns up and finance megawatt chargers at every motorway burger bar – or it can let electrons and molecules share the load.

The data are dull but decisive: a combined battery-hydrogen roadmap slashes costs, soothes supply chains and lands the climate target without gridlock.

Winners, plural, are cheaper, cleaner and more resilient than a winner-takes-all fantasy.

Ignore that, and the bill starts at roughly five trillion euros.