Inside an electrolyser stack: four materials battles shaping green hydrogen costs

If you’ve ever seen a hydrogen electrolyser in the flesh – which you probably haven’t, unless you have an unusual job or a hobby involving guided tours of industrial sheds – you’ll know that, from the outside, it’s a fairly boring box.

Grey, perhaps. A bit whirry. It doesn’t look as though it’s going to save the world.

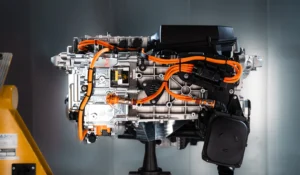

But peel back the casing, go past the pipes and valves, and right in the middle you’ll find the cell stack, which is where the wizardry – or more accurately, the chemistry – happens.

Now, as the name suggests, the stack is not one single thing. It’s a collection of very thin sandwiches made up of catalysts, coatings, separators and membranes. From above it sort of looks like the closed pages of a book.

It’s these unglamorous layers that decide how efficiently you can turn electricity into hydrogen, how long the thing will last before it corrodes, and how much precious metal you’ll need to keep it all working.

Most of the cost, and much of the technical risk, lies right there in the stack.

Over the years, four main designs of electrolyser have emerged. There’s alkaline, the oldest and most straightforward, which runs in a warm bath of caustic electrolyte.

There’s PEM, which swaps the liquid bath for a solid polymer membrane and can respond very quickly to fluctuating power.

There’s AEM, a sort of hybrid that tries to combine the cheap materials of alkaline with the responsiveness of PEM.

And then there’s solid oxide, which takes the opposite approach and runs the whole lot at furnace temperatures so you can make use of industrial waste heat.

Each of these families has its own set of headaches, and engineers are constantly fiddling with the materials inside in an attempt to solve them.

Alkaline (AEL): faster coatings, better diaphragms

Alkaline electrolysers are the old warhorses. They’ve been bubbling away since the mid-20th century, and the basic idea hasn’t changed much. Basically, you immerse a pair of electrodes in a potassium hydroxide solution and apply electricity until hydrogen comes off one side and oxygen off the other.

Because the chemistry is fairly forgiving you can get away with using cheap metals, mostly nickel, which is why this type is still popular for large plants.

The snag is that alkaline is less efficient than newer designs, so people have been prodding it in search of small improvements.

The electrodes, for example, can be upgraded from plain nickel plates to alloys such as nickel-molybdenum or nickel-cobalt, which react more enthusiastically.

A few manufacturers even sprinkle in tiny amounts of platinum or ruthenium, just to liven things up.

And then there’s the way those catalysts are applied. Traditionally you had to coat and bake the electrodes several times over, which is rather like making puff pastry – tedious, energy-hungry, and not something you’d want to do at scale.

A company called Jolt Solutions has devised a process called Sparkfuze, which uses an exothermic reaction to stick the catalyst on in one go, saving both time and electricity.

Separating the gases is another challenge. For years the industry has relied on a material called Zirfon, a sort of ceramic-plastic composite that lets ions through but keeps hydrogen and oxygen apart. It works well, but others are now experimenting with different routes.

Novamem, for example, makes diaphragms by embedding nanoparticles in a polymer and then dissolving them out again, leaving a controlled network of pores for the liquid electrolyte to pass through.

It’s intricate stuff, but the sort of marginal gain that could make alkaline competitive for longer.

PEM (PEMEL): iridium thrift and PFAS pressure

Proton exchange membrane electrolysers are the younger, flashier cousins. Instead of sloshing liquid around, they use a thin solid polymer membrane as the electrolyte, which means they can start up quickly and cope with power that goes up and down with the wind or the sun.

That’s why they’re being built into all the renewable-hydrogen projects you keep hearing about.

But that glamour comes at a price. The membrane needs platinum on one side and iridium oxide on the other, and neither of those is what you’d call cheap.

Iridium, in particular, is rarer than hen’s teeth – global supply is measured in tonnes rather than kilotonnes – and if every PEM project in the pipeline went ahead tomorrow, we would run out almost immediately.

Hence the frantic efforts to make iridium go further – blend it with ruthenium, spread it more thinly, stick it on a support, anything that reduces the loading without ruining performance.

There is also the small matter of the membrane itself. At present, most are made from per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, PFAS for short, which are excellent at conducting protons but are also under the regulatory cosh because they don’t break down in the environment. “Forever Chemicals “is their nickname you’ll have most likely heard.

Developers such as Ionomr Innovations are therefore working on hydrocarbon-based alternatives, which are cleaner but trickier.

The thinner you make them, the better they conduct, but the more likely they are to allow hydrogen to sneak through, which is both wasteful and unsafe.

To keep things intact, manufacturers reinforce them with expanded Teflon or high-temperature plastics like PEEK.

It’s a delicate balancing act, with conductivity, durability and safety, all tugging in different directions.

AEM (AEMEL): PFAS-free by design

Anion exchange membrane electrolysers are a bit of a mongrel, borrowing features from both alkaline and PEM but, crucially, dispensing with PFAS altogether.

Instead they use hydrocarbon backbones doped with quaternary ammonium groups, which ferry hydroxide ions from one side of the cell to the other.

In principle it’s elegant, combining low-cost catalysts with fast response. In practice, early membranes tended to fall apart, which rather spoilt the effect.

That problem is gradually being solved. Chemical companies such as AGC and Fumatech, and start-ups like Versogen and Ionomr, are now producing membranes that can actually last long enough to be useful.

But even here, design choices are still being thrashed out. One camp favours “dry cathode” systems that look very much like PEM, with gas diffusion layers and catalysts painted directly onto the membrane.

The other prefers “wet cathode” systems, where electrolyte is fed to both electrodes and nickel transport layers are used on each side. Both approaches have their merits, and the industry hasn’t yet decided which will win.

Solid oxide (SOEC): hotter and tougher

Finally, we come to solid oxide electrolysers, which are at once the most exotic and the most brutal.

They run not in warm baths or on delicate polymers but at furnace temperatures – around 600-900°C degrees Celsius, in fact, where the ions hop through a ceramic lattice.

The advantage is very high efficiency, especially if you can borrow heat from a nearby industrial process, and the possibility of producing syngas or e-fuels directly.

The disadvantage is that not much likes being cycled between room temperature and 800°C degrees, day after day, without cracking.

To deal with this, some developers have moved towards metal-supported cells. Ceres Power, for example, coats the active layers onto a porous stainless-steel sheet, which provides mechanical strength while allowing the working layers to be much thinner.

Others are trying to ease the thermal burden by bringing the operating temperature down a notch.

Replacing the planetary-sounding yttria-stabilised zirconia electrolyte with gadolinia-doped ceria allows operation closer to 600°C, which is less punishing, though it also means re-engineering the electrodes. A company called Topsoe has already commercialised systems on this basis.

Outlook: small wins, multiplied by gigawatts

Individually, none of these changes seems revolutionary. A slightly different alloy here, a marginally better membrane there, a new method of applying catalyst powder to a sheet of metal.

But stack them all together and multiply by the gigawatts of electrolysers that governments now expect to see built, and the effect becomes very large indeed.

Research firm IDTechEx reckons the annual market for components will exceed ten billion dollars by 2036, which is a useful reminder that in the hydrogen world, the big battles are often fought at the microscopic level.