A small town in Washington state makes its own hydrogen fuel for only $4 per kg

In a quiet pocket of central Washington, where the Columbia River winds its way through fruit orchards and high desert, a small public utility has pulled off something that much of the hydrogen world still insists is too expensive to be done.

They’ve built a fully functioning, publicly accessible green hydrogen station – and they’re selling fuel at four dollars per kilogram. You read that right, four bucks per kilogram.

Cheaper than anyone else

That price – which is 75-90% below current retail rates in the US – hasn’t come from a billion-dollar investment fund, a global OEM partnership, or a multi-state hydrogen hub.

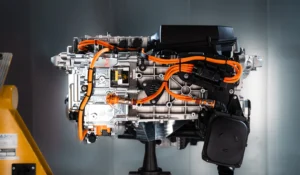

It’s come from a plucky little rural electric utility company that owns its own hydro dam and decided to build a 5 MW electrolyser.

At first glance, it’s a local project. But under the surface, it may be one of the clearest and most credible proofs yet that small-scale, distributed hydrogen production can work – technically, economically, and operationally – in the real world.

The site is modest in scale, which is by design. The electrolyser on site runs on surplus power from the nearby Wells Hydroelectric Project – a 774 MW generating asset also owned by Douglas PUD.

When grid demand falls below the hydro plant’s output, Douglas PUD faces a choice: it can either reduce generation by adjusting flow through the turbines – which adds mechanical wear and limits operational efficiency – or find a productive use for the surplus power.

By routing that electricity into an electrolyser, the utility avoids repeated cycling of its generating equipment and creates a controllable load that can respond dynamically to grid conditions.

A controllable load, not just a fuel source

The result is lower maintenance demand on the hydro plant, improved grid stability, and a steady supply of renewable hydrogen produced during periods when that electricity would otherwise be undervalued or curtailed.

The result is a clean fuel produced on-site using zero-carbon electricity – with no need for compression trucks, liquefaction, or long-distance distribution. From power to pump, everything happens within a few miles.

And the economics reflect that. With electricity making up around 80% of electrolysis input costs, access to low-cost hydropower – especially at off-peak times – gives Douglas PUD a fundamental structural advantage.

The $4/kg price is not a loss leader. It’s what it costs them to make the hydrogen.

A community system that works

The East Wenatchee facility is a local system, built around local needs, optimised for grid support and early fleet adoption. It’s not an attempt at building an industrial level site.

Toyota Mirai vehicles leased by the utility use the station regularly. A hydrogen-powered bus is in operation. And capacity planning is already underway for future expansion. The Sheriff even drives a Mirai.

Much of the hydrogen industry is still built around scale. Large centralised production facilities, long-haul distribution, megawatt-class refuelling stations, and economies of scale that depend on major off-takers.

That model may be essential for heavy industry and long-distance logistics – but it’s also high-risk, capital intensive, and infrastructure heavy.

Douglas PUD takes a more quaint approach, by matching hydrogen production with existing renewable generation and local consumption, meaning the utility has avoided many of the barriers that slow down or inflate the cost of hydrogen elsewhere.

Part of a grid strategy

There’s no grid constraint issue, because the power is already there. There’s no transport problem, because the hydrogen doesn’t leave the site. There’s no revenue model mismatch, because the utility is not a private company chasing returns – it’s a public service using public assets to reduce emissions and improve operational flexibility.

In that sense, this is not just a hydrogen project. It’s a grid project. And that may be where its long-term value lies.

It won’t replace every refuelling need. It’s not a model for long-haul aviation or ammonia export.

But it’s a tangible, working answer to a much simpler question: what if local hydrogen production didn’t have to be so difficult?